“Only in Comedy is it the general tendency for all the characters to be brought to light and reconciled, to produce the story’s closing image of a little world wholly united.”

– Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots

We arrive at the fifth entry in our exploration of music through the framework of Christopher Booker’s Seven Basic Plots: Comedy. In Booker’s view, comedy is not defined by laughter alone, but by its arc. It’s a journey that moves from confusion and separation toward clarity and renewal. At its heart, it is the story of a world set off balance, gradually restored. Mistaken identities are unmasked, misunderstandings are resolved, and relationships are mended. The curtain falls, and all is well again.

Booker grounds this structure in the traditions of classical comedy, including the tangled plots of Shakespeare and, musically, in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. For our exploration, we turn to a less conventional example (one that also aligns with our mission at Cadenza, as we will be hosting a symposium on this very composer and work, making this an especially timely reflection).

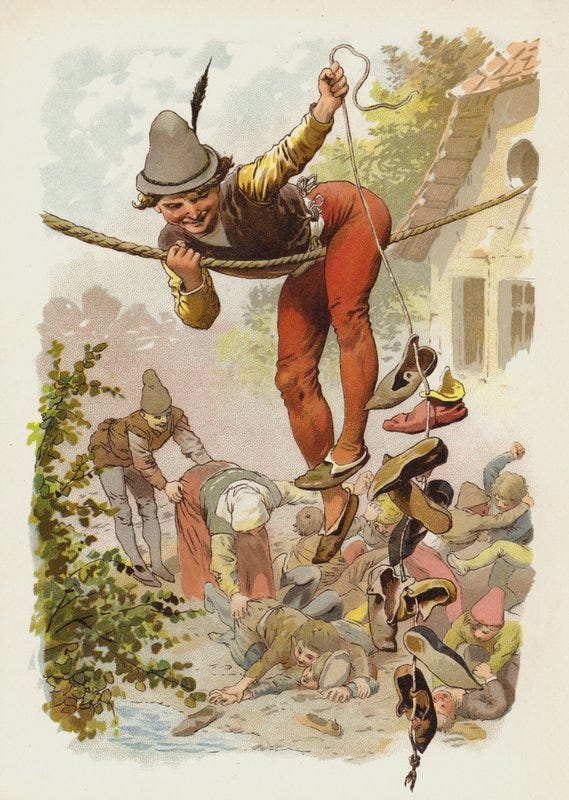

Our focus is Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Richard Strauss’s irreverent tone poem based on the legendary German folk figure. Till is part jester, part anarchist. He is an agent of disorder who pokes at institutions, challenges expectations, and reveals uncomfortable truths. In Strauss’s music, the orchestra becomes his playground, and we as listeners are drawn into his antics with both delight and unease.

Booker outlines key stages of the comedic narrative:

A Confused and Uncertain World

The Confusion Worsens, Pressure of Darkness Increases

Things Come to Light…

…A Joyful Ending

Let’s follow Till through this arc. Although his story may not seem traditionally comic, it contains the essential shape that defines the structure. Booker also explores the nature of “darkness” in these stories. Sometimes it comes from others, sometimes from within the hero, and sometimes it stems simply from confusion. In this case, Till is the source of his own darkness. His antics create the very consequences he must face. He must lie in the bed he made.

Stage 1: A Confused and Uncertain World

Strauss opens the work with musical signals of instability. A six-note sigh from the strings, a solo horn suggesting mischief, and finally the clarinet introduces Till himself. We meet the sly irreverent trickster! The world we enter is one of playful confusion. Till disrupts order, mocks authority, and uses disguise to slip between identities; the variations of his theme gives us the clues for this. He calls to mind Shakespeare’s Puck from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, another character who turns confusion into clarity by first deepening the chaos.

Stage 2: The Confusion Worsens, Pressure of Darkness Increases

Rather than romantic entanglements or mistaken identity, the conflicts in this story arrive in the form of pranks (the title of our piece!). Till rides through a market on horseback, impersonates a priest, flirts with women, and mocks scholars. Each episode is vividly portrayed through Strauss’s musical storytelling (readers may recall this musical technique in our previous exploration of Strauss’s Don Quixote). The “Till theme” threads through these scenes, a mischievous signature that tells us he remains in control even as he invites chaos.

And throughout, we feel on the verge of some “darkness”. Surely the people can’t (won’t?) let these antics continue?

Stage 3: Things Come To Light…

Our fears are realized. The musical adventures take us to a climax: the capture and trial of Till. Chaos gives way to consequence. We hear this in a funeral march, low brass providing the heft and weight to signify the moment. His theme falters, turning towards desperation, at the same time a few jaunts from the woodwinds tell us to hold on to his nature as a joke maker. The court sees through it, and he is sentenced to execution.

Stage 4: …A Joyful Ending

Joyful ending? Sort of. In this piece, we don’t get a traditional reconciliation. Till is condemned and executed. A sharp pizzicato marks the snapping of his neck. The music offers no reprieve.

And, yet, Strauss offers a final word. After the execution, the original six-note sigh returns. Our world has returned to some stability. Then comes one last outburtst from the orchestra, as if Till has managed a final prank from beyond the grave. The ending feels light rather than tragic. Though our hero has vanished, his presence remains; the spirit of irreverence has not been extinguished!

There are many operas and stories that follow the comic pattern more precisely. They resolve misunderstandings through marriage, return characters to their rightful places, and send the audience home smiling. Till Eulenspiegel does something more subversive. It shows us a world momentarily upended and asks us to consider the value of the one who upends it.

In this sense, it may be closer to the essence of comedy than it first appears. Though it lacks a traditional happy ending, it still reveals something true. It reminds us that mischief and laughter are not distractions from truth, but one of its oldest messengers. There is wisdom from the fool. And in the case of this particular fool and this music, it is hard not to leave with a smile!