“In fact we might almost say that, for a story to resolve in a way which really seems final and complete, it can only do so in one of two ways. Either it ends […] united in love. Or it ends in death.”

– Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots

Following our exploration of Comedy in Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots, it feels only natural to pivot to its narrative twin: Tragedy. While Comedy resolves in clarity and renewal, Tragedy moves in the opposite direction. Despite the moments of joy and despite any best intentions, the ultimate finality is the death of our hero – there is no other way out.

We think, of course, of Shakespeare’s most famous works such as Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello. We may also recall the foundational Greek tragedies like Oedipus Rex and Antigone. These stories do not simply involve misfortune. They present a pattern where the hero’s fall is assured. Fate, character flaw, or the forces of the world ensure there is no escape.

In music, we certainly have a deep history with the idea of tragedy. We’ve seen it in operas such as Carmen (discussed in Booker’s book) and Tosca, and we’ve seen it in the many musical interpretations of the Bard’s works, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet as a notable example.

Music is no stranger to this narrative. Tragedy surfaces in operatic finales like Carmen and Tosca, and in symphonic works inspired by literature, such as Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. But the most affecting musical tragedies are not those that borrow a storyline. They are the ones that arise from within, born of personal reckoning and lived experience.

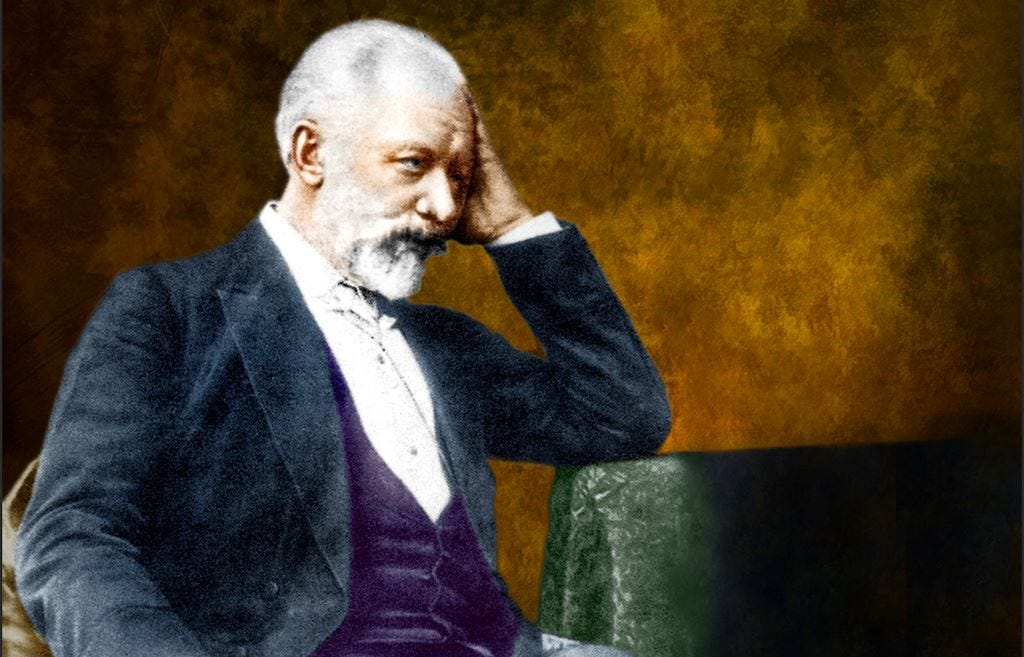

Few composers embody this more fully than Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Throughout his life, he endured so much hardship turmoil – family relationships, financial hardships, and the pressure of concealing his homosexuality in a repressive society. His music often feels like an open wound. It reaches directly into the heart and speaks with honesty; it makes us laugh, it makes us tremple, it makes it definitely makes us cry.

So it should come as no surprise that if we want to study the idea of tragedy, we look to his music, and nothing more prominent than his final work, his 6th symphony, known as the Pathétique. Tchaikovsky wrote this piece later in life, and most surely was aware of his own mortality by this point. In fact, just 9 days after the premiere of this work, he died, somewhat enigmatically (most historians now seem to agree that it was of rapid onset cholera from impure water, but other more conspiratorial theories still remain).

Booker outlines five stages that define the tragic arc:

Anticipation – The hero identifies a goal or desire.

Dream – That goal seems within reach.

Frustration – Obstacles emerge, and things begin to unravel.

Nightmare – The situation worsens, fate closes in.

Destruction or Death Wish – The hero is undone, often fatally.

Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique follows this structure with uncanny clarity.

Stage 1: Anticipation

The symphony opens quietly. The low strings create a sense of uncertainty, and soon a dialogue emerges with the winds, tender and searching. We catch glimpses of joy, though the mood remains fragile. Then, around four minutes in, we are given a melody that soars – one that stands among the most beautiful themes in the repertoire. But this peace is short-lived.

An abrupt (to say the least!) bang and the orchestra begins a fight with and against each other. The music becomes a struggle, as if the forces of love and death are fighting for dominance. And yet, we get a glimpse of hope in the middle of this war, the strings rising to the heavens, the brass answering the call. It’s at once a hopeful moment as it is a cry for help.

Remain hopeful! Tchaikovsky gifts us his melody again, which largely carries us through the balance of the movement, which ends with a reflective coda. Our object of desire – perhaps it’s love - is still in view.

Stage 2: Dream

The second movement dances lightly. Though written in 5/4 time, it maintains a graceful sway, suggesting that happiness might be achievable. There is optimism here. Things are good, the world is ours to have.

In the third movement, the mood shifts again. A triumphant march carries us forward with confidence. The goal seems within reach. The music builds to a dazzling climax, and in many performances, audiences applaud here, thinking the symphony has ended. Tchaikovsky has played one of his greatest tricks, giving us the illusion that we’ve reached resolution.

But we haven’t…

Stages 3–4: Frustration and Nightmare

The final movement begins, and the tone changes instantly. Grief sets in. The strings pull downward, step by step, drawing us into darkness. The earlier triumph is revealed as hollow. The melody aches. The orchestration becomes sparse. Flickers of hope appear, but they vanish quickly. The mask of joy slips, and we are left with what lies beneath: sorrow, longing, and despair. We were indeed tricked in the third movement; it becomes clear that the ending will not be a happy one.

Stage 5: Destruction or Death Wish

As the final pages unfold, the our world begins to fade away. Instrument by instrument, voice by voice. The music lowers to the grave and fades into silence. Our hero, perhaps Tchaikovsky himself, is gone, drifted off into nothing.

The Pathétique is not simply a tragic story set to music. It is a tragedy lived and expressed in sound. Tchaikovsky does not dramatize someone else’s fall. He offers his own vulnerability, grief, and farewell. In doing so, he composes one of the most personal and powerful tragedies in music.

As listeners, we do more than hear the music. We accompany the hero - Tchaikovsky himself - on his final journey. And through this journey, we are reminded of what it means to be human, to desire, to fail, and to face the end with honesty and grace.