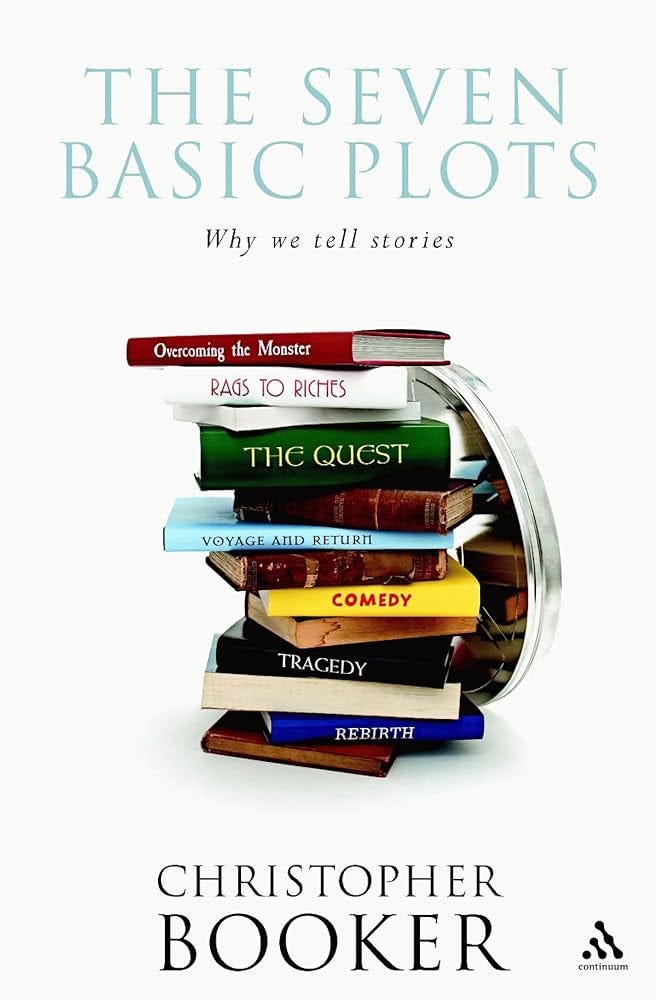

A few months ago, I stumbled upon an idea to explore through writing from a chance encounter with a wonderful composer working on some new pieces. We were discussing musical structures the lens of “narratives” and “journeys”, and it reminded me of Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots. Booker’s thesis is that nearly all stories – from ancient myths and Gilgamesh to fairy tales, Shakespeare, and modern cinema – follow one of seven narrative structures. Sometimes it’s a hero going on a quest, sometimes it’s the journey from nothing to abundance, and sometimes it’s a series of misadventures along the way to a happy ending.

It is these very structures that draw us in; we relate to how they unfold and are drawn in to the journey they take us on.

As I reflected on that conversation and Booker’s framework, I felt a connection to the intersection of the two, a core idea at the heart of everything we do at Cadenza. What if orchestral music, even when not overtly programmatic, contain these same storytelling patterns? If we get past the intellectual musical structures of sonata, rondo, symphonies, concertos, can we find narrative journeys? In doing so, would that enhance our connection to the music and draw even more meaning for us? These questions became the basis for a writing exploration.

Over the course of several articles, I tested this theory. For each of Booker’s seven plots, I considered many possible musical candidates, ultimately choosing one work to explore in depth. I compared its musical structure to the narrative arc Booker describes, then examined how specific musical elements align with the plot’s key moments.

What I found is that there is something here. Great music can be seen through the lens of telling a story – even if they are not explicitly defined as attempting to do so. Great music has characters, conflicts, transformations, highs and lows, and resolution. We find heroes, villains, sidekicks, mentors, we find adventures, we find humor, we find hope, we find despair, and we find sadness and tragedy. These are not just abstract forms, these are stories told through music. Just as powerful and timeless as we find in literature.

As a quick recap to my journey, out of considering hundreds of pieces of music across it all, I landed on the following:

Overcoming the Monster – Symphony No. 7 (“Leningrad”) by Shostakovich

Rags to Riches – Piano Concerto No. 1, 3rd Movement by Tchaikovsky

The Quest – Don Quixote by Strauss

Voyage and Return – Symphonie Fantastique by Berlioz

Comedy – Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks by Strauss

Tragedy – Symphony No. 6 (“Pathétique”) by Tchaikovsky

Rebirth – Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”) by Mahler

It’s curious to me that in this list, we find two pieces by Strauss and two by Tchaikovsky. As I tried to take each of the structures independently, it is purely by chance that there were some repeated composers. In the case of Tchaikovsky, perhaps this isn’t so much a surprise. His music is so emotive and expressive, that a connection to storytelling arcs feels very clear. Likewise, Strauss’s music, especially his tone poems, are so closely tethered to a human experience and story – it is for this reason that I’m so excited to study him further in our next Cadenza Conversation.

Ultimately, this exploration affirmed something I’ve long suspected: music tells stories. Even when the story isn’t named, it can be found. And perhaps that’s why great music continues to move us, through the timeless shape of a journey we somehow already know.